40 years later, still a mystery: Where is Johnny Gosch?

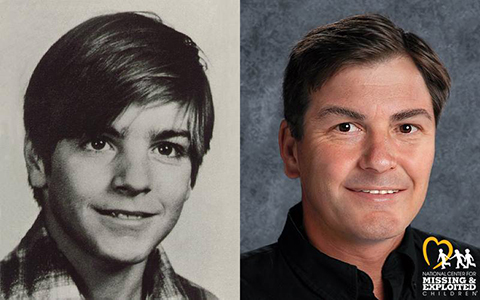

When a 12-year-old paperboy named Johnny Gosch disappeared on the job in West Des Moines, Iowa at the crack of dawn on Sept. 5, 1982 – 40 years ago – America was just beginning to awaken to the problem of missing and sexually exploited children in this country.

Three years earlier in 1979, Etan Patz, 6, vanished while walking to his school bus in New York City. Adam Walsh, also 6, was abducted in 1981 from a shopping mall in Hollywood, Florida and later found murdered. Kathy Kohm, abducted in 1981 at age 11 from Santa Claus, Indiana, was raped and murdered. More than two dozen children, including 9-year-old Yusuf Bell, were abducted from 1979 to 1981 in what became known as the “Atlanta child murders.”

“Across the nation, children are being sexually assaulted, murdered, forgotten,” a call-to-action symposium held in Louisville, Kentucky declared in its preamble in 1981, the year before Johhny vanished. “Unfortunately, the press, law enforcement officials, politicians and the general public are unaware of just how common the problem is in every part of the country, and many children die singly and obscurely, their silent deaths lost to the American conscience.”

The landmark symposium, attended by the parents of Etan, Adam, Kathy and Yusuf, became a catalyst for the creation of the National Center for Missing & Exploited Children (NCMEC) and provided a blueprint for what would become a coordinated national response when a child is missing or sexually exploited. Less than a year later, on Oct. 12, 1982, then-President Reagan signed the Missing Children Act to “address the tragedy of America’s missing children” and reassure parents that every effort would be made to find their children.

When Johnny disappeared from his quiet suburb on Sept. 5, 1982 as he was starting his Sunday morning paper route, his parents, Noreen and John Gosch, had few resources to help them find their son. There were no national missing children hotlines, no AMBER Alerts, no geo-targeted missing posters, no rapid deployment teams, no DNA databases. It would be two more years before NCMEC, founded by Adam’s parents, John and Reve Walsh, and other child advocates, opened its doors.

Johnny would be 52 years old today. The 40-year mystery – Where is Johnny? – has spawned a raft of conspiracy theories, documentaries, movies, books, Podcasts and enough headlines to fill the newspapers he once delivered on Sunday mornings and after school, a rite of passage for many kids at the time. Parents everywhere began realizing their children should not be left alone, especially in the dark, and pulled them closer.

“I still think of Johnny as a 12-year-old boy, not a 50-year-old adult,” his dad said in an interview with KCCI News 8 in Des Moines to mark the passage of 40 years. “What I think of most is, I cannot believe someone has not come forward with information or something.”

Johnny was wearing a white sweatshirt when he vanished that morning and that detail is “locked in my mind,” he said. Whenever he’s driving and see’s something white in a ditch, he instinctively looks over to see what it is. He said he has “no idea” what happened to his son.

KCCI Reporter Todd Magel, who has covered the case from the very beginning, asked Noreen what she believes happened to her son. She said that, based on information she has been able to verify, that he was abducted doing his paper route and “was put into what they now call human trafficking.”

Johnny’s mother became a life-long child safety advocate, warning the public about child predators and pushing for better laws locally and nationally. She and her husband lobbied Iowa legislators, and the “Johnny Gosch Bill” was passed requiring law enforcement’s immediate involvement in missing children cases in the state. Other states followed suit.

On that fateful Sept. 5 morning, after his brother tapped on his door to make sure he was up, Johnny set off in the pre-dawn hours for his paper route accompanied by his dog, Gretchen. His parents only found out he was missing after one of Johnny’s customers called to complain that he did not get his Sunday paper.

Johnny’s father headed out and found his son’s red wagon, abandoned and still filled with bundles of the Des Moines Sunday Register. Police and the community helped search for the 5-foot-7 boy with light brown hair and blue eyes. Initially, police said, they suspected Johnny had been abducted and a search was conducted. But when he could not be located, they began to believe that he had run away. Today, he is presumed to have been abducted.

After her son had been missing for about 15 years, Noreen dropped a bombshell. She said she knew what happened to Johnny – that he had escaped his captors and visited her at her apartment with an unidentified man. She said her son, then an adult, told her he had been a victim of a pedophile ring and was cast aside when he was too old. Fearing for his safety, he assumed a new identity and could not return home, she said.

Johnny’s father, who had been divorced from Noreen for years, has stated publicly that he’s not sure if such a visit occurred. Law enforcement has never confirmed it, and there has been speculation that the visit could have happened – but, if it did, it was likely someone pretending to be Johnny, which, sadly, sometimes occurs in long-term missing cases.

Despite good intentions, Pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock thought displaying missing children on milk cartons would frighten children at the kitchen table. Other ways to share missing children photos, including on grocery bags, were used instead.

Despite good intentions, Pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock thought displaying missing children on milk cartons would frighten children at the kitchen table. Other ways to share missing children photos, including on grocery bags, were used instead.

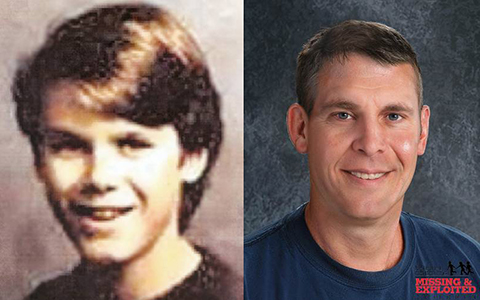

Johnny was among the first of the so-called “milk carton kids” whose faces were placed on milk cartons in the hope that someone sitting at their kitchen table having cereal had seen the missing children. He was pictured on a milk carton next to another paperboy, 13-year-old Eugene Martin, who vanished two years after Johnny under nearly identical circumstances.

Eugene also went missing at the start of his paper route in the early-morning hours of Aug. 12, 1984 in nearby Des Moines which adjoins Johnny’s suburb. His newspaper bag filled with bundles of the Des Moines Sunday Register was also left behind. Both boys worked for the same newspaper and vanished without a trace. This time, federal and local law enforcement turned out in force.

Despite the striking similarities, law enforcement has not connected the two cases. Nor has a third case in the area been linked. Two years after Eugene disappeared, on March 29, 1986, Marc Allen, 13, vanished on his way to a friend’s house in Des Moines. Except for the fact that Marc was not a paperboy, all three cases occurred in the same general area in the 1980s and remain unsolved.

“Really sad that there was never a resolution to Johnny Gosch’s case – no body, no clues, no suspects,” said John Walsh, longtime host of America’s Most Wanted and now In Pursuit with John Walsh. “We were involved in that case from the beginning and profiled him I don’t know how many times On America’s Most Wanted. I always believed there was a serial pedophile kidnapper in that area.”

Four decades later, the search for Johnny – and the other two boys – is not over. NCMEC believes that new technologies and genetic testing might provide his family with some answers if DNA from relatives could be obtained. If Johnny is still alive, there could be children, even grandchildren.

Sgt. Jason Heintz, with the West Des Moines Police Department, said some detectives have spent their entire careers investigating Johnny’s abduction and are now helping the younger generation pick up where they left off. Tips still come in every year, he said, and they are fully investigated. Four decades later, there are four boxes of evidence in the case at police headquarters, he said.

“Our goal has always been the same,” said Heintz. “We want nothing more than to solve the case and bring closure to the family and to all those who knew and loved Johnny.”

Said Walsh: “My heart goes out to the family. I always say that not knowing is the worst.”

If you have any information, please contact the West Des Moines Police Department on its tip line at 515-222-3399 or NCMEC at 1-800-THE-LOST (1-800-843-5678.)